Editor's note: The Bruce Museum of Arts and Science

provided source material to Resource Library for the following article

or essay. If you have questions or comments regarding the source material,

please contact the Bruce Museum of Arts and Science directly through either

this phone number or web address:

Weaving a Collection: Native

American Baskets from the Bruce Museum

February 10 - June 10, 2007

The Bruce Museum in

Greenwich, Connecticut, highlights its Native American basket collection

in a new exhibition that opens Saturday, February 10,  2007,

and runs through Sunday, June 10, 2007. Weaving a Collection: Native

American Baskets from the Bruce Museum explores five geographic regions

of basketry: the Northeast, Great Plains, Southwest, California, and Northwest.

On view are approximately 45 examples from all the major basket makers of

North America that illustrate the distinctive elements of technique and

materials from these regions. The show focuses on the differences in forms

and materials among tribal affiliations and geographical regions and examines

the evolution of basketry following the arrival of the collector. (right:

Pomo Gift Basket, California, 19th century, 5 _ h x 14 d x 19 c inches,

One rod coiling; horizontal "V" motifs and blue seed beads. Bruce

Museum collection 19908)

2007,

and runs through Sunday, June 10, 2007. Weaving a Collection: Native

American Baskets from the Bruce Museum explores five geographic regions

of basketry: the Northeast, Great Plains, Southwest, California, and Northwest.

On view are approximately 45 examples from all the major basket makers of

North America that illustrate the distinctive elements of technique and

materials from these regions. The show focuses on the differences in forms

and materials among tribal affiliations and geographical regions and examines

the evolution of basketry following the arrival of the collector. (right:

Pomo Gift Basket, California, 19th century, 5 _ h x 14 d x 19 c inches,

One rod coiling; horizontal "V" motifs and blue seed beads. Bruce

Museum collection 19908)

Basketry has been a part of the rich tapestry of Native

American cultures for centuries. Native American basket weavers have transformed

twigs, grasses, roots, ferns, and bark into works of art that are unsurpassed

for their beauty and technological skill. Basket weaving is one of the oldest

known Native American arts. Archaeologists have identified some ancient

American Indian baskets from the Southwest as being nearly 8,000 years old.

As with most Native American art, a multitude of distinct

traditions became established in North American basketry. Different tribes

used different materials, weaving techniques, basket shapes, and characteristic

patterns. Northeast Indian baskets, for example, are traditionally made

out of pounded ash splints or braided sweet grass. As native people were

displaced from their traditional lands and lifestyles, their traditional

tribal basket-weaving styles started to change as they adapted to new materials

and absorbed the customs of new neighbors. In places like Oklahoma, where

many tribes were interned together, fusion styles of basket weaving arose.

However, unlike some traditional native crafts, the original diversity of

Native American basket styles is still very much  evident

today. (right: Yokut rabbit dancers, Yokut, California, 19th century,

4 h x 8 d x 24 _ c inches, Coiled sedge, three rabbit dancers. Bruce Museum

collection 21291)

evident

today. (right: Yokut rabbit dancers, Yokut, California, 19th century,

4 h x 8 d x 24 _ c inches, Coiled sedge, three rabbit dancers. Bruce Museum

collection 21291)

Based on early evidence, we know that prior to contact

with European cultures, the basket-making tribes of North America had created

a repertoire of basket shapes and design elements specific, if not unique,

to each tribal grouping. Tribal customs and artistic traditions dictated

that basketry styles remain relatively constant over time, with little emphasis

on experimentation or innovation. The volatile impact that Euro-Americans

had on native cultures was eventually reflected in the material culture

of the tribal groups, basketry being no exception. These newcomers to North

America had little interest in Native American basketry until the late 19th

century, when the belief arose that the native cultures might soon disappear.

Motivated by this sentiment, some individuals began collecting Native American

cultural material with an enthusiasm and appreciation previously unknown.

Before these early collectors entered the arena, some Native

American basketry had already begun to exhibit change as evidenced by the

appearance of trade items incorporated into the baskets such as glass beads,

commercial yarns, and exotic feathers from the ostrich and peacock. However,

these new materials were utilized in the traditional manner as decorative

elements merely substituting for native-made clamshell beads and wild bird

feathers.

As collectors became more discerning about the quality

of a basket's weave and exhibited a preference for particular types of designs

and shapes, the weavers responded to this new market. Graceful and distinctive

shapes such as bottleneck baskets and more literal design elements

such as human figures or animal forms (which replaced the often more sophisticated,

abstract designs) were in great demand in the early collector market. However,

these basketry shapes and design motifs were only produced by a few tribal

groups and then only occasionally. Thus, borrowing shapes and motifs from

other tribal groups became, if not commonplace, at least an acceptable practice

among some of the weavers. This phenomenon ushered in a new period of experimentation

and creativity while it maintained the on-going high standards of technical

and artistic expertise.

(above: Makah lidded box, Makah, Northwest Coast, Olympic

WA, 19th century, 3 h x 4 d x 13 _ c inches, Shallow circular lidded box,

crescents on lid, natural and dyed grasses. Bruce Museum collection 20940)

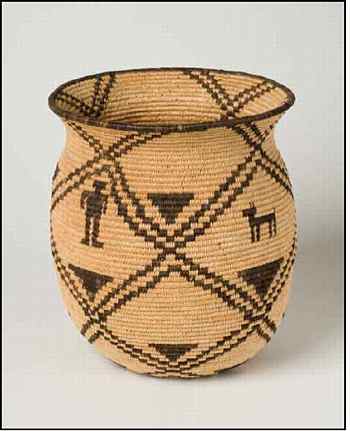

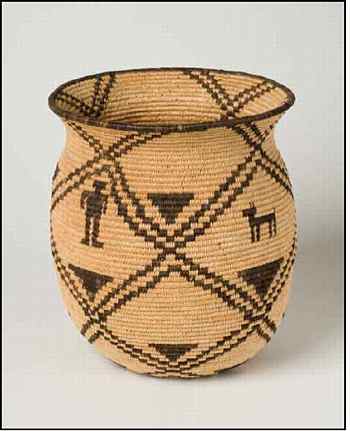

(above: Apache, Southwest, Arizona, early 20th century,

10 h x 8 _ d x 32 _ c inches, Food storage olla, human motifs. Bruce Museum

collection 20963)

(above: Washoe, Great Basin, Nevada, early 19th century,

5 _ h x 11 _ d x 37 c inches, Classic bowl, native use patina, geometric

design. Bruce Museum collection 67.03.36)

Public programs

- Sun., March 4, 3 p.m. Music at the Bruce 2007 Young People's

Concert Series: Native American Music. Joseph Fire Crow, Jr. and Music

of the Northern Cheyenne. Renowned Northern Cheyenne musician Joseph

Fire Crow, a Grammy nominee and 3-time Native American Music Award winner,

performs on drum and flute, and sings traditional and contemporary music.

This concert is the first in a series of three musical education programs

designed for children ages 6 years and up and their parents/guardians.

These programs are suitable for people of all abilities. Fee. Reservations

suggested; call the Museum at (203) 869-0376. Future concerts take place

March 18, and April 15 (see calendar for details).

-

- Sun., March 11, 3 p.m. Makah Basket Weaving: Basketry

of the Northwest. Melissa Peterson, or Walsibot, her family name,

is an enrolled member of the Makah Tribe. She lives on the Makah Indian

Reservation in Neah Bay, Washington, where she is a master artist and teacher

in Makah traditional arts: basket weaving, drum making, jewelry making

and storytelling. She will present a lecture on Ozette weaving techniques

and her experiences as a basket maker. Reservations are recommended by

calling the Museum at (203) 869-0376. Free with Museum admission.

-

- Sun., March 18, 3 p.m. Music at the Bruce 2007 Young

People's Concerts: Native American Music. Cochise Anderson. M. Cochise

Anderson, Chickasaw/Mississippi Choctaw, is a musician, actor, playwright,

storyteller and educator. Described as "a new voice for a new age,"

Cochise Anderson will perform traditional song with contemporary themes

and original music. Second in a series of three concerts designed for children

in grades 1-5 and their parents/guardians. These programs are suitable

for people of all abilities. Fee, per concert, reservations strongly recommended;

call the Museum at (203) 869-0376. (Final concert in the series takes place

April 15. See calendar for details.)

-

- Sun., April 15, 3 p.m. Music at the Bruce 2007 Young

People's Concerts: Native American Music. Jana. This year's Grammy

nominee for "Best Native American Music" album, Jana, has a powerful

voice coupled with the sensibilities of pop, R&B, world, and gospel

music. The last of three concerts designed for children in grades 1-5 and

their parents/guardians. These programs are suitable for people of all

abilities. Fee, reservations strongly recommended by calling the Museum

at (203) 869-0376.

-

- Tue. - Fri., April 17, 18, 19, 20, 10:30 a.m. April Vacation

Workshops: Native American Baskets. Students in grades 1 - 3 will

explore the Museum's exhibition Weaving a Collection: Native American

Baskets from the Bruce Museum and then work on related craft projects.

- Tue.: Raffia Baskets

- Wed.: Northeast Splint Bark Baskets

- Thurs.: Coil Baskets

- Fri.: Yarn Baskets

- Fee. Includes all materials. Reservations are required;

call the Museum (203) 869-0376.

- Individualized/modified workshops for individuals with

special needs will run from 1 - 2 p.m. each day. Call the Director of Education

at (203) 869-6786, ext. 325, for reservations. Fee.

-

- Sun., April 22, 1 - 4 p.m. Native American Family Day.

Activities for the whole family include gallery hunts, hands-on crafts.

At 3 p.m. Leaf Arrow Storytellers from Arts Horizons presents Native American

Storytelling. Donna Couteau Cross and Joe Cross perform a program of storytelling,

song and traditional dance exploring the lives and culture of the Native

American people past and present. All activities are free with Museum admission.

Editor's note: RL readers may also enjoy:

Read more articles and essays concerning this institutional

source by visiting the sub-index page for the Bruce

Museum in Resource Library.

Visit the Table

of Contents for Resource Library for thousands

of articles and essays on American art.

Copyright 2007 Traditional Fine Arts Organization, Inc., an Arizona nonprofit corporation. All rights

reserved.

2007,

and runs through Sunday, June 10, 2007. Weaving a Collection: Native

American Baskets from the Bruce Museum explores five geographic regions

of basketry: the Northeast, Great Plains, Southwest, California, and Northwest.

On view are approximately 45 examples from all the major basket makers of

North America that illustrate the distinctive elements of technique and

materials from these regions. The show focuses on the differences in forms

and materials among tribal affiliations and geographical regions and examines

the evolution of basketry following the arrival of the collector. (right:

Pomo Gift Basket, California, 19th century, 5 _ h x 14 d x 19 c inches,

One rod coiling; horizontal "V" motifs and blue seed beads. Bruce

Museum collection 19908)

2007,

and runs through Sunday, June 10, 2007. Weaving a Collection: Native

American Baskets from the Bruce Museum explores five geographic regions

of basketry: the Northeast, Great Plains, Southwest, California, and Northwest.

On view are approximately 45 examples from all the major basket makers of

North America that illustrate the distinctive elements of technique and

materials from these regions. The show focuses on the differences in forms

and materials among tribal affiliations and geographical regions and examines

the evolution of basketry following the arrival of the collector. (right:

Pomo Gift Basket, California, 19th century, 5 _ h x 14 d x 19 c inches,

One rod coiling; horizontal "V" motifs and blue seed beads. Bruce

Museum collection 19908) evident

today. (right: Yokut rabbit dancers, Yokut, California, 19th century,

4 h x 8 d x 24 _ c inches, Coiled sedge, three rabbit dancers. Bruce Museum

collection 21291)

evident

today. (right: Yokut rabbit dancers, Yokut, California, 19th century,

4 h x 8 d x 24 _ c inches, Coiled sedge, three rabbit dancers. Bruce Museum

collection 21291)